Nib #10: Give Your Idea an Origin Story

The best part of any superhero’s mythology is the beginning. Superman vs. Lex Luthor? Meh. Baby Kal-El, the last son of doomed Krypton, rescued and exiled to a strange world far away, where he must be hidden and protected from his enemies until he grows into his destiny? Now that’s the stuff.

So it is with persuasive writing. The most compelling part of a persuasive argument is its origin story.

You can’t just lunge right in with “Pass a flat tax!” or “Ban TikTok!” or “Get rid of the designated hitter!” First of all, people may not even know what you’re talking about. And second, your target audience of unpersuaded-but-persuadable readers is likely to bristle at such bluntness.

Roman rhetoricians called the “beginning of the story” phase of persuasive structure the “contextio,” the context. They understood that to sell someone on a solution, you first have to tell the story of the problem in such a way that your solution seems the best one.

The most obvious approach is to go back in time. Persuasive writing frames today’s problems in the past tense.

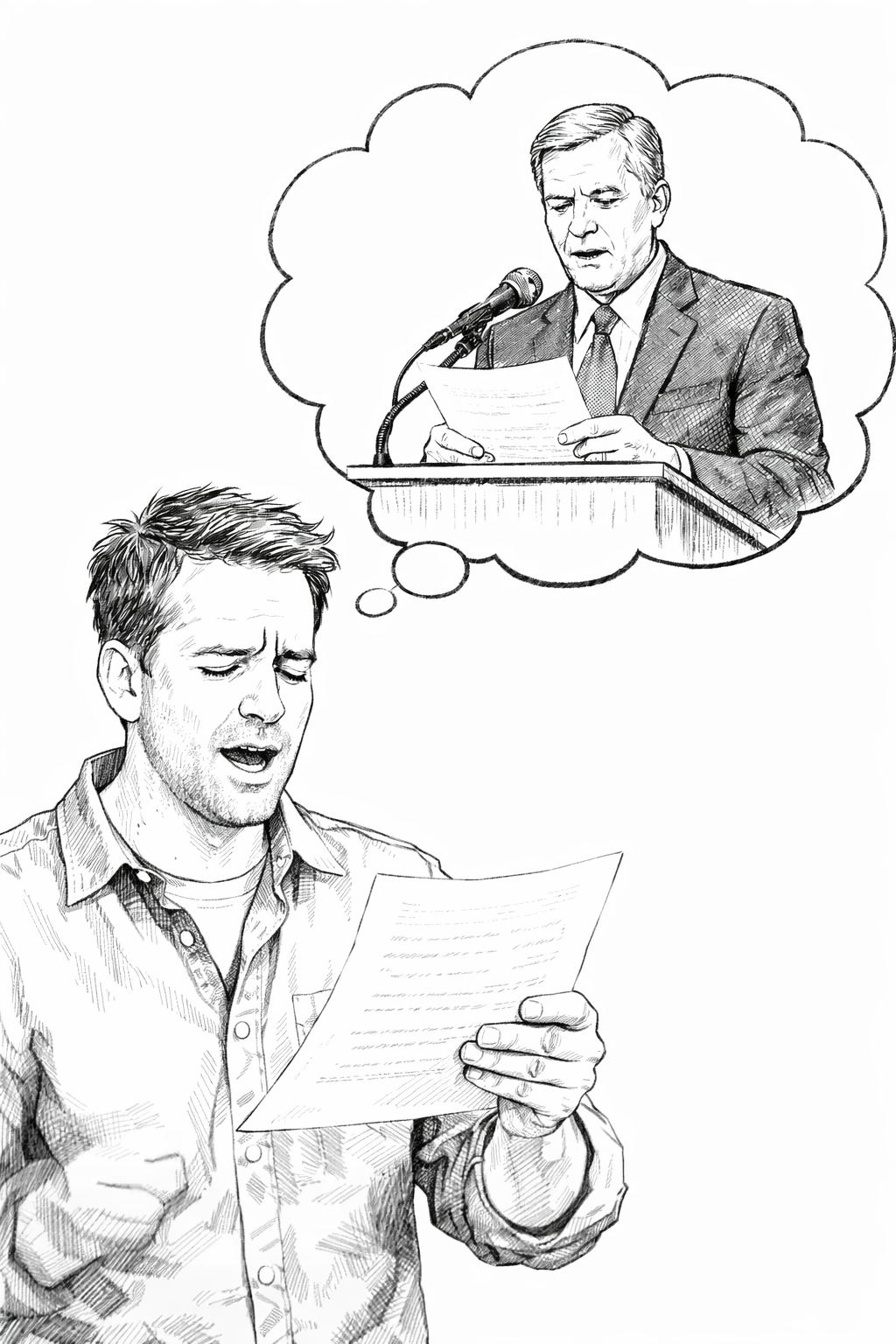

In 1863, when Abraham Lincoln set out to justify his then-controversial twofold strategy in the Civil War — union-restoration and emancipation — he began his argument, “Four score and seven years ago…”

In 1963, when Martin Luther King tried to win white Americans over to the then-controversial cause of civil rights, he opened his case by reminding the country of the Emancipation Proclamation. “Five score years ago,” King began his "I Have a Dream" speech.

When Michael Corleone provokes Hyman Roth in The Godfather, Part II — “Who had Frank Pentangeli killed?” — do you remember how Roth responds? In the past tense, telling the story of his friendship with Moe Greene: “There was this kid I grew up with.”

For an idea of how old this trick is, consider that Pericles’ funeral oration in 431 B.C., after a few sentences of throat-clearing, begins, “I will speak first of our ancestors.”

Advocating a new idea without an origin story is like hanging a new window without a frame. Persuasion depends on empathy. Empathy is about shared stories. And good stories have good beginnings.

Give your idea a good origin story, and your readers will give them a more receptive hearing.

Until next week… Keep writing!