Nib #76 Workshopping J.D. Vance's Munich Speech, Part I

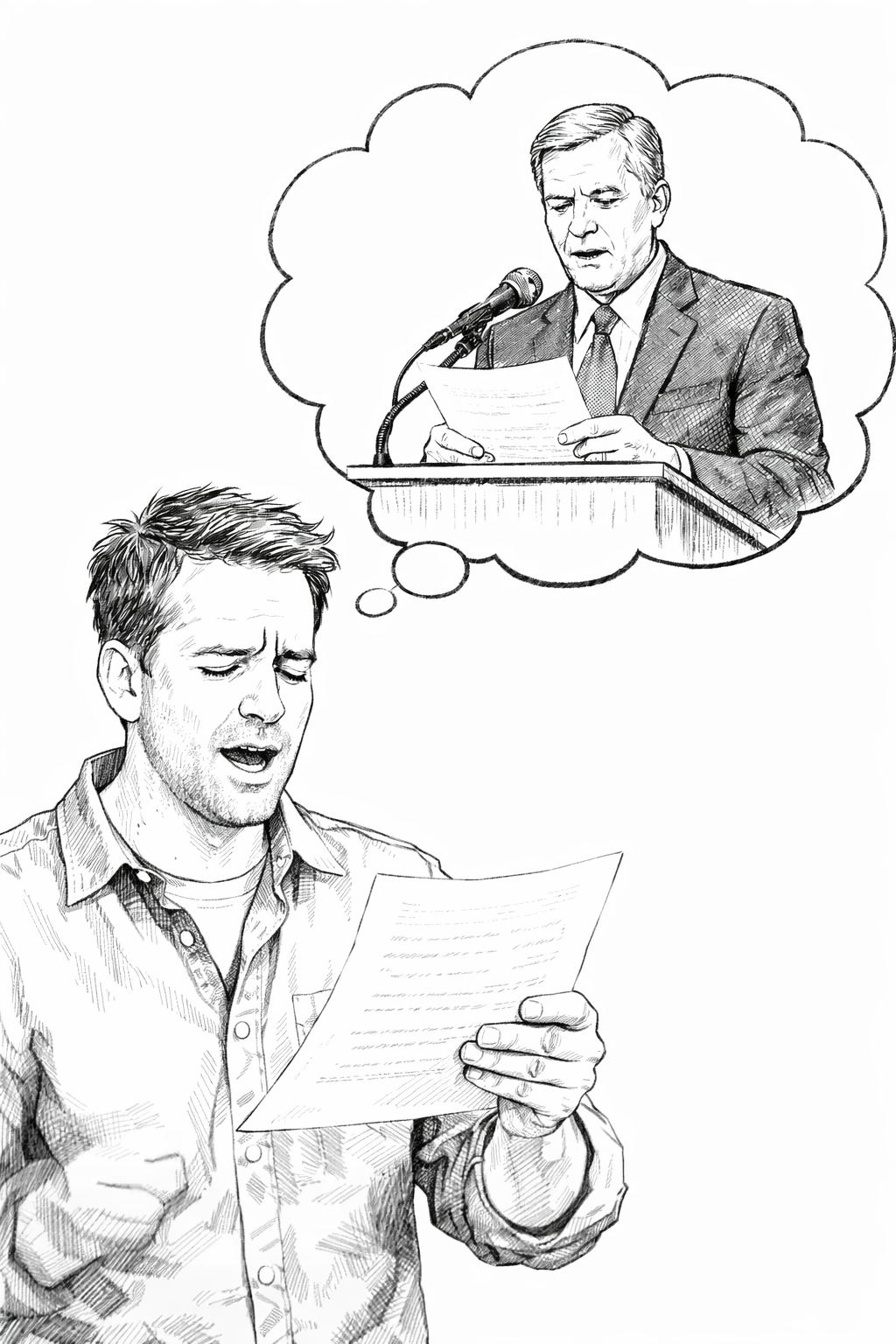

Last week’s Nib presented the five parts of classical rhetorical structure in one convenient speechwriting cheat sheet. For the next few Nibs, we’ll see what that structure looks like in practice, with a close reading of the most talked about speech of the year (so far!): Vice President J.D. Vance’s February remarks to the Munich Security Conference.

Vance’s speech made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic for its stringent criticism of our European allies’ retreat from free speech and democracy. (You can watch the speech here and read the full text here.) Pundits have understandably focused on the substance and strategy of Vance’s speech.

Aspiring speechwriters should focus instead on its structure — because the speech’s framing is one of the reasons it had such an impact.

Let’s start with Part I: The Introduction.

Remember, the purpose of a speech’s intro is to grab the audience’s attention. The best way to do this is usually with a clear, direct statement of the speech’s thesis. By announcing up front the problem the speaker wants to highlight, the solution he’s proposing, or both, a good intro simultaneously makes a speech more persuasive and the audience more persuadable.

Did Vance?

Well, the vice president opens his remarks with 300 words of pleasantries. That feels like a lot. On the other hand, it was a long speech. In Munich, Vance was technically his audience’s guest. And he knew that in a few minutes he’d be ripping them. There was also some breaking news about a terrorist attack that required some sensitive attention, too. So in this case, the longer-than-normal windup was appropriate.

Notice, though: once Vance gets into his formal remarks, he goes all-in:

“But while the Trump administration is very concerned with European security and believes that we can come to a reasonable settlement between Russia and Ukraine, and we also believe that it's important in the coming years for Europe to step up in a big way to provide for its own defense, the threat that I worry the most about vis-à-vis Europe is not Russia, it's not China, it's not any other external actor. And what I worry about is the threat from within, the retreat of Europe from some of its most fundamental values -- values shared with the United States of America.”

Boom.

No hedging. No bank shots. Right out of the shoot, Vance unequivocally tells his audience — European leaders, the U.S. media, etc. — exactly what this speech is going to be about.

Task #1 is accomplished: he has their attention.

The lesson for aspiring speechwriters here is simple: resist the urge to ease into your argument. Don’t fumfer around. It’s not disarming; it’s annoying. One of the greatest signs of respect a speaker can show his audience is to not waste their time.

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941…”

“First in war, first in peace, first in the hearts of his countrymen…”

“If we are mark’d to die, we are enow / To do our country loss; and if to live, / The fewer men, the greater share of honour.”

You only a have few seconds to win your audience’s attention. Don’t waste them on throat-clearing. Sentence one, paragraph one: light the candle. Clearly announce your intention so that you can then get into the narrative of your argument — where the persuasive process really begins.

Next Nib, we’ll look at Part II of Vance’s speech: The Beginning of the Story.

Until next week… keep writing!