Nib of the Week

Writing Tips for Young Conservatives from Inkling Communications

January 30, 2026

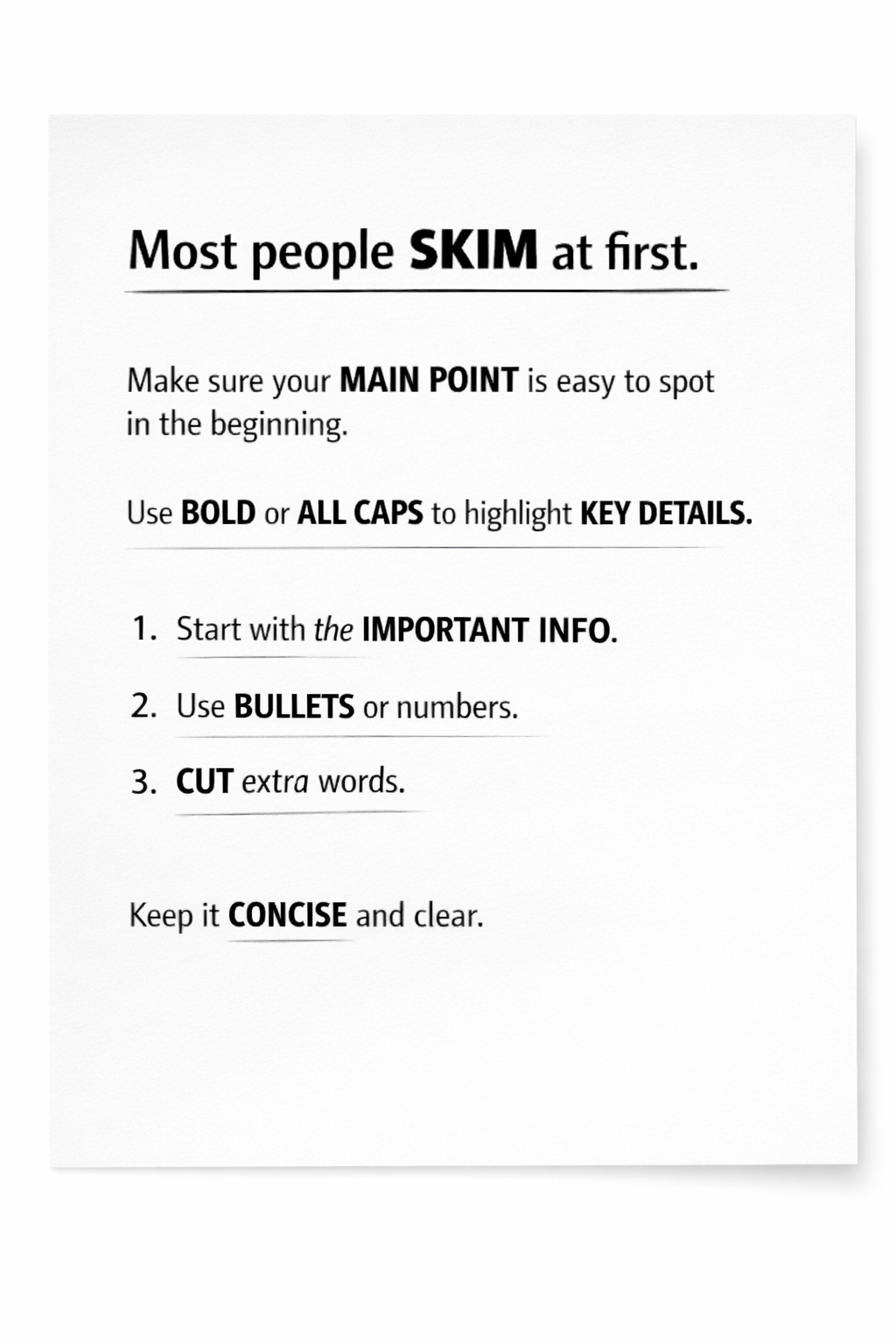

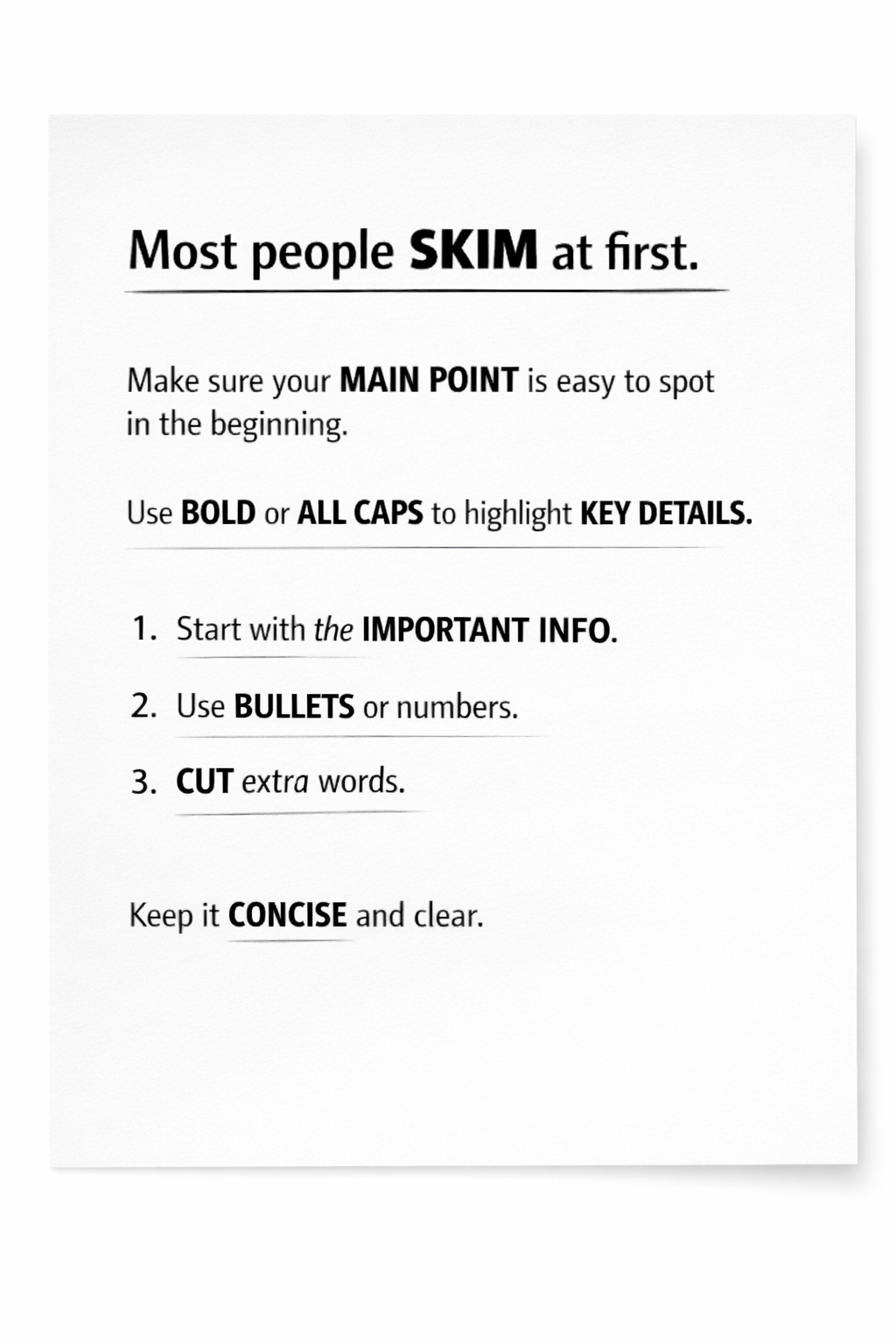

Most people don’t read with deep concentration and attention, at least not at first. They skim. Young writers should anticipate this and tailor their writing for busy, distracted, half-interested audiences. The best formats to skim-Proof are non-urgent things we read quickly and silently, like: Work emails Memos Office reports Announcements & invitations To Skim-Proof your writing, try these four strategies: Front-load important information, ideally in your first sentence. Use bold letters and ALL CAPS to highlight key details. Indent numbered and bulleted lists to make long sentences and paragraphs easier to read. Edit out extraneous words and sentences. Don’t think of Skim Proofing as surrendering to our attention-deficit culture. Think of it as a literary deep core exercise. Because front-loading content, streamlining text, and breaking up long paragraphs will strengthen all your writing — even longer, closely read forms — over time. Until next week… keep writing!

January 23, 2026

When young writers ask, ”What should I read to improve my writing?” they usually mean, “Who?” And of course, there are plenty of great literary stylists young writers can learn and steal from. But for young writers in 2026 — betrayed by our thumbless education system and beset by screen distractions — the Who doesn’t matter as much as the When . If you really want to improve your writing, adhere to a simple rule: The majority of what you read every day should be more than 24 hours old. This is not to say good writers only read 19th century English novels or Homeric epics. There is plenty of great writing being produced right now. But it's not on Twitter. Don’t surrender your reading habits to an algorithm, especially an algorithm designed to make you awful. Read books. Read essays. Read poems. Read movie reviews. Yes, the quality of what you read matters. But what matters more is that you choose what you read and not the other way around. Until next week… keep writing!

January 16, 2026

Everyone knows the active voice is usually preferable to the passive voice. But most young writers are never taught why. Here are the two main reasons: 1. The passive voice is meandering. It tends to make sentences longer and harder to follow. Passive: The Constitution is something that should be followed by Congress. Active: Congress should follow the Constitution. These two sentences convey the same thought. But see how the first one is cumbersome, and almost condescending in its tone? Readers hate that. 2. The passive voice is slippery. Passive: That should not have happened. Active: I should not have done that. See how the second sentence there feels sincere and accountable while the first feels like a non-apology? That’s the passive voice at work. By deprioritizing — or outright eliminating — the subject of a sentence’s verb, it obscures responsibility for the sentence’s action. The passive voice isn’t evil. It just tends to make your sentences harder to read and you harder to trust. Until next week… keep writing!

January 9, 2026

We already covered the Magic Trick ( Nib #100 ), reading your work out loud. And its clarity corollary ( Nib #101 ), reading your work out loud as the audience . This last application of the Magic Trick is for anyone who writes for someone else: read your work out loud as your principal . It’s not necessary that every sentence perfectly mirror your boss’s patois. What’s necessary is that the writing not sound like someone else. (Especially you !) Don’t make references or use words or tell jokes or stories that your principal wouldn’t. The third time you read your the work out loud, imitate the person actually speaking or signing the text. When you trip over a phrase — however perfect it sounded in your head — or when a word choice snags like a fingernail on a blanket, change it. That’s how you put the ghost in ghostwriting. Until next week… keep writing!

January 2, 2026

Happy New Year! To kick off Year Three of the Nib, here are three can’t-miss New Year’s resolutions to improve your writing in 2026. 1. Memorize one poem per month. Poetry is literary protein — writing at its most nutritive and muscle-building. To truly benefit from a poem, you have to know it by heart. If you’re not sure where to start, you can’t go wrong with the King James Version of Psalm 23. 2. Read a Jane Austen novel. It doesn’t matter which, but Pride and Prejudice is Pride and Prejudice for a reason. 3. Delete one shiftless, no-account word or phrase from your writing. Good options include vague intensifiers like very or significant, robot verbs like affect or engage , and clunky stutter-steps like the fact that or in terms of . Really want to make the world a better place in 2026? See if you can go the whole year without writing the word impactful . Until next week… keep writing!

December 26, 2025

Merry Christmas, and — now — Happy Thank You Note Season! Thank You Notes might seem like a perfunctory, mechanical writing format. But they are as powerful a training ground as any prose project young writers can tackle. Think about it. The four qualities of a good Thank You Note are cornerstones of all good writing: Concision : Thank You cards’ small sizes preclude rambling. They force writers to get to the point and stay on it. Specificity : Thank You notes demand concrete details. You don’t thank someone for “that thing you got me” or “that kind gesture.” No, you specify what you’re thankful for, exactly how and when you’re using it, and the particular good it has done. Authenticity : Expressing gratitude may be the most human thing human beings can do. Thank You notes by necessity draw out our truest voices. They sound like us — or rather, like the best version of ourselves. Generosity: Thank You notes have no purpose other than to graciously serve their audience. Writing them exercises virtues that can strengthen all our writing, whatever the format, going forward. The lessons of Thank You Note writing may be hidden, but they’re true and good. They’ll make you a better writer — in more ways than one. Until next week… keep writing!

Sign up here to receive a new Nib every Friday

Sign up here to receive a new Nib every Friday

Thank you for registering for Nib of the Week notifications. Check your inbox every Friday!

Oops, there was an error registering. Please try again.

January 30, 2026

Most people don’t read with deep concentration and attention, at least not at first. They skim. Young writers should anticipate this and tailor their writing for busy, distracted, half-interested audiences. The best formats to skim-Proof are non-urgent things we read quickly and silently, like: Work emails Memos Office reports Announcements & invitations To Skim-Proof your writing, try these four strategies: Front-load important information, ideally in your first sentence. Use bold letters and ALL CAPS to highlight key details. Indent numbered and bulleted lists to make long sentences and paragraphs easier to read. Edit out extraneous words and sentences. Don’t think of Skim Proofing as surrendering to our attention-deficit culture. Think of it as a literary deep core exercise. Because front-loading content, streamlining text, and breaking up long paragraphs will strengthen all your writing — even longer, closely read forms — over time. Until next week… keep writing!

January 23, 2026

When young writers ask, ”What should I read to improve my writing?” they usually mean, “Who?” And of course, there are plenty of great literary stylists young writers can learn and steal from. But for young writers in 2026 — betrayed by our thumbless education system and beset by screen distractions — the Who doesn’t matter as much as the When . If you really want to improve your writing, adhere to a simple rule: The majority of what you read every day should be more than 24 hours old. This is not to say good writers only read 19th century English novels or Homeric epics. There is plenty of great writing being produced right now. But it's not on Twitter. Don’t surrender your reading habits to an algorithm, especially an algorithm designed to make you awful. Read books. Read essays. Read poems. Read movie reviews. Yes, the quality of what you read matters. But what matters more is that you choose what you read and not the other way around. Until next week… keep writing!

January 16, 2026

Everyone knows the active voice is usually preferable to the passive voice. But most young writers are never taught why. Here are the two main reasons: 1. The passive voice is meandering. It tends to make sentences longer and harder to follow. Passive: The Constitution is something that should be followed by Congress. Active: Congress should follow the Constitution. These two sentences convey the same thought. But see how the first one is cumbersome, and almost condescending in its tone? Readers hate that. 2. The passive voice is slippery. Passive: That should not have happened. Active: I should not have done that. See how the second sentence there feels sincere and accountable while the first feels like a non-apology? That’s the passive voice at work. By deprioritizing — or outright eliminating — the subject of a sentence’s verb, it obscures responsibility for the sentence’s action. The passive voice isn’t evil. It just tends to make your sentences harder to read and you harder to trust. Until next week… keep writing!

January 9, 2026

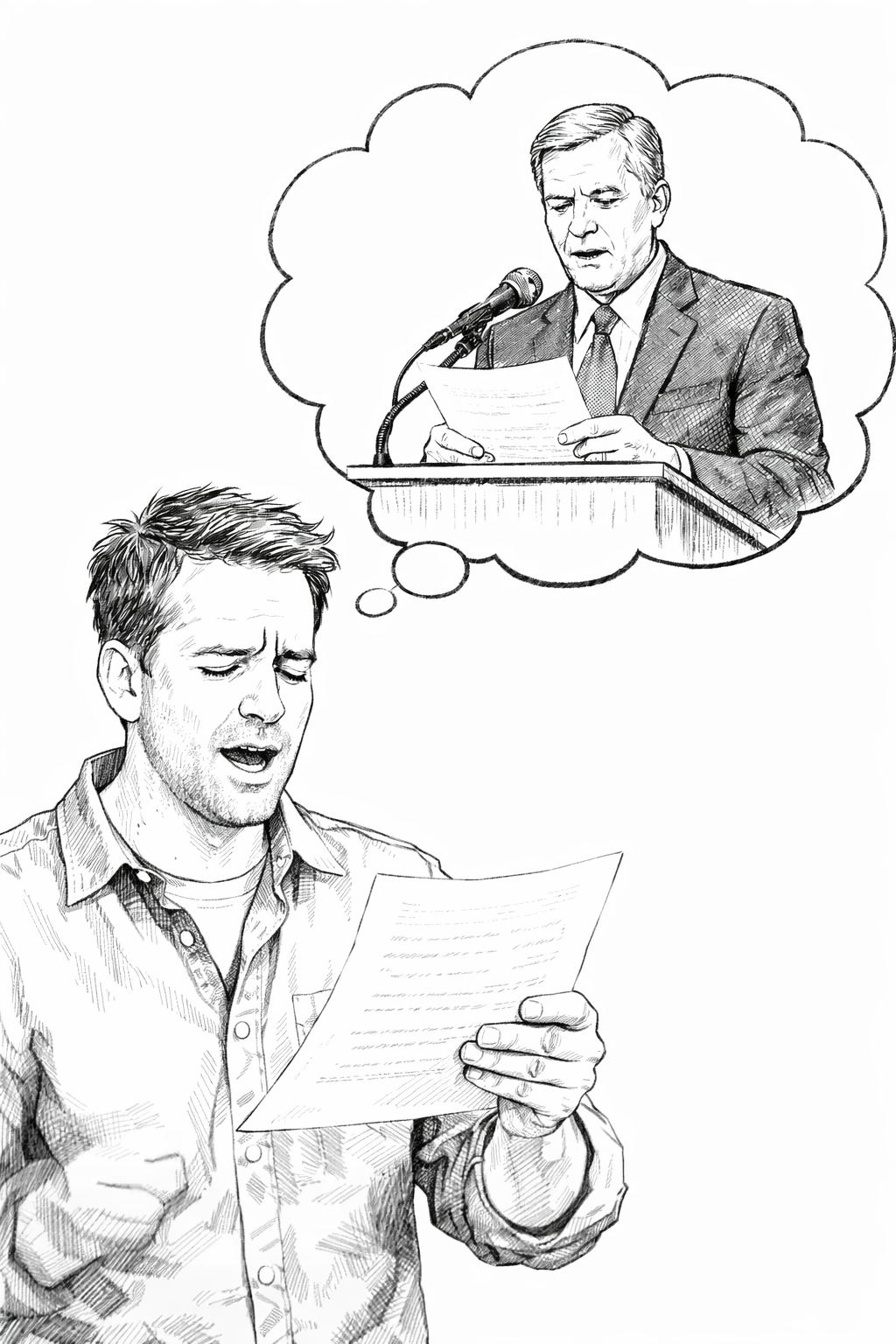

We already covered the Magic Trick ( Nib #100 ), reading your work out loud. And its clarity corollary ( Nib #101 ), reading your work out loud as the audience . This last application of the Magic Trick is for anyone who writes for someone else: read your work out loud as your principal . It’s not necessary that every sentence perfectly mirror your boss’s patois. What’s necessary is that the writing not sound like someone else. (Especially you !) Don’t make references or use words or tell jokes or stories that your principal wouldn’t. The third time you read your the work out loud, imitate the person actually speaking or signing the text. When you trip over a phrase — however perfect it sounded in your head — or when a word choice snags like a fingernail on a blanket, change it. That’s how you put the ghost in ghostwriting. Until next week… keep writing!

Sign up here to receive a new Nib every Friday

Sign up here to receive a new Nib every Friday

Thank you for registering for Nib of the Week notifications. Check your inbox every Friday!

Oops, there was an error registering. Please try again.