Nib #72 The Secret to Writing About Policy Details

The secret to writing persuasively about policy details is to not write about policy details.

To explain.

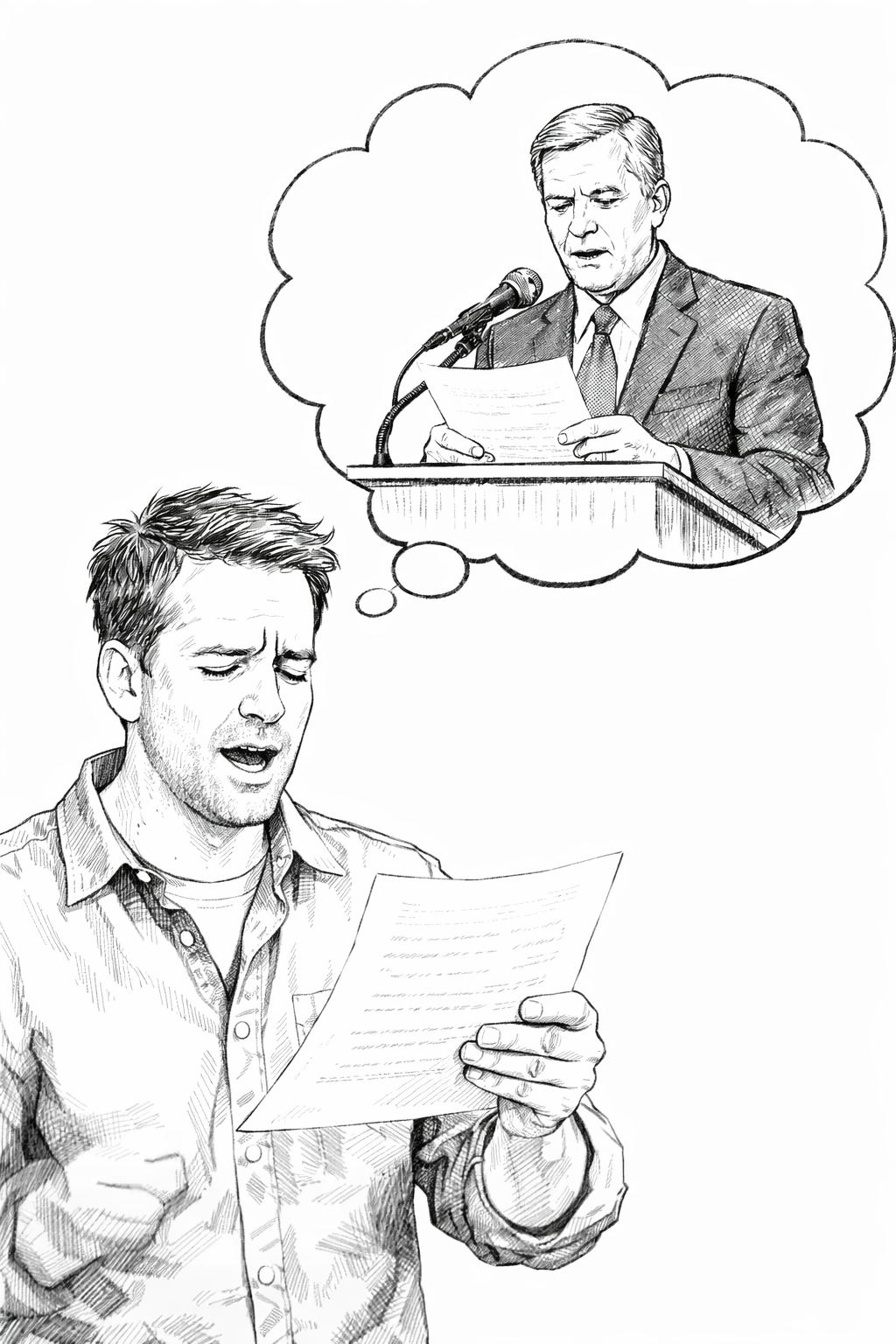

Substance is the fourth of the five traditional parts of persuasive argumentation structure. If you’ve done your job with the first three - the Introduction (Nib #71), Origin Story (Nib #10), and Future Stakes (Nib #70) — the substance should become mostly incidental.

Remember, with the Introduction, all you’re trying to do is get your audience’s attention by highlighting the problem you’re trying to solve or the solution you’re offering. Then, if you tell a compelling backstory about where today’s problem came from, you’ll win the audience’s trust and empathy. Finally, if you paint an appealing picture of an imaginary future in which we did and/or didn’t adopt your solution, you’ll start to win their enthusiasm.

If you do all that, then your specific solution is no longer just a candidate or a bill or an amendment or strategy. Rather, your solution becomes a bridge — from the unhappy present to a happier future.

That’s what public policy debates really are. They’re competitions to define our problems, their true sources, and what kind of future we want to build. As a matter of governing, the solutions — the How We Get There part — are paramount. As a matter of persuasive argument, however, those details matter far less.

Like a bridge. People don’t care whether a bridge is arched or cantilevered or suspended. They only care if it will get them to where they want to go.

This bridge-building mindset also helps writers with the always knotty question of “How much substantive detail do I need to include here?” The answer: only as much as is needed to win the specific points your framing raises.

Let’s say you’re advocating a school choice reform — an issue awash in arguments for and against. If you frame your argument around test scores and greater opportunities for classical curricula, then your Substance section should hit those points and mostly ignore the others. Show how your plan will connect your audience to higher scores and Great Books programs, and deprioritize things like costs, values education, parental authority, etc.

As always, your focus should be on what your audience needs to hear, not what you — or your policy staff — want to say. Different audiences and different writing projects have different purposes. So a speech pushing school choice to parents might feature a different frame than an op-ed aimed at state legislators — and so should emphasize different details. And of course sometimes — as in a think tank white paper or legislative memo — the audience may be so expertly familiar with the topic that the granular analysis is the point. In each case, what matters is intentionality -- write for your audience, not about a topic.

Policy details should always serve your writing, rather than the other way around. Give the audience enough substance to support your narrative — but not so much that the argument collapses of its own weight.

Again, like a bridge.

Until next week… keep writing!