Nib #95 When to Take it to Eleven

Senate Republican Leader John Thune gave the most memorable speech of his long congressional career this week when he blew up at Democrats over the ongoing government shutdown:

“SNAP recipients shouldn’t go without food. People should be getting paid in this country. And we’ve tried to do that 13 times! You voted no 13 times! This isn’t a political game. These are real people’s lives that we’re talking about. And you all just figured out, 29 days in, that oh, there might be some consequences?”

It was the first time most Americans have ever heard Thune raise his voice. Indeed, it’s the first time the Nib can remember the famously unflappable Thune so nearly flapped!

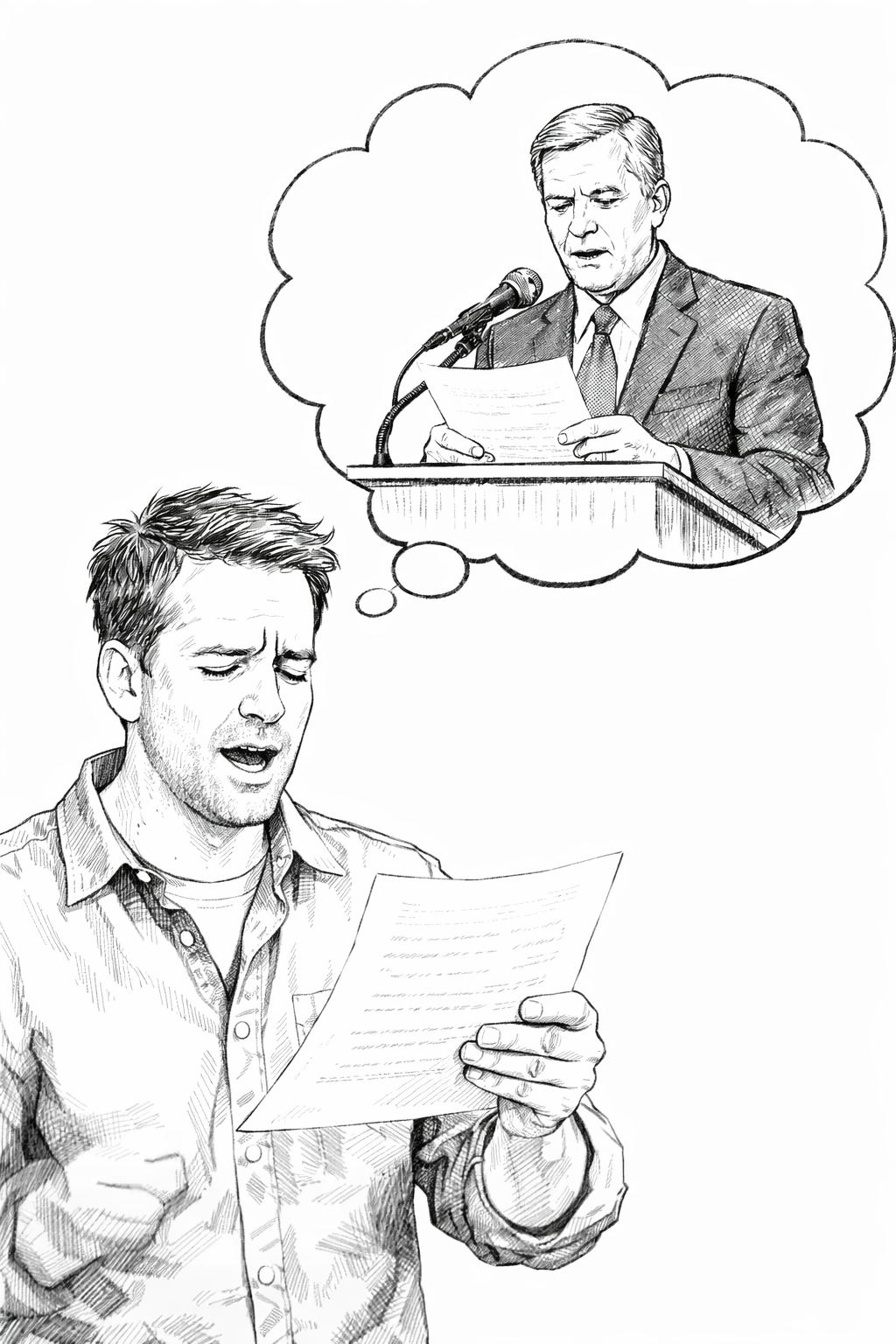

Young speechwriters, take note: the reason Thune’s anger resonated here is that he so rarely expresses it. He usually avoids the cheap hysterics and hyperbole that poison our public discourse and desensitize Americans to real outrages.

Anger is a legitimate weapon in every writer’s arsenal. But it dulls with overuse. People whose main rhetorical tactic is histrionic fury may get their share of clicks in the short term. But over time, they persuade no one.

Red meat only works when it’s part of a balanced rhetorical diet. Writers should use anger intentionally, strategically, and sparingly. Like the time mild-mannered New York Times columnist Ross Douthat went after Planned Parenthood’s supposed “pro-life” bona fides or Michael Kelly’s medieval takedown of Bill Clinton after his Monica Lewinsky speech.

Those classic pieces, like Thune’s speech Wednesday, worked because their authors’ reputations for reasonableness lent their outrage credibility. Per Morton Blackwell’s classic rule of political advocacy, they only got mad on purpose.

Young writers who want their own barbs stick one day should take a similar approach. Master the art of winsome, generous democratic persuasion — so that when you need to take it to eleven some day, it will help and not hurt your cause.

Until next week… keep writing!