Nib #20: Jerry Seinfeld and the Power of Framing

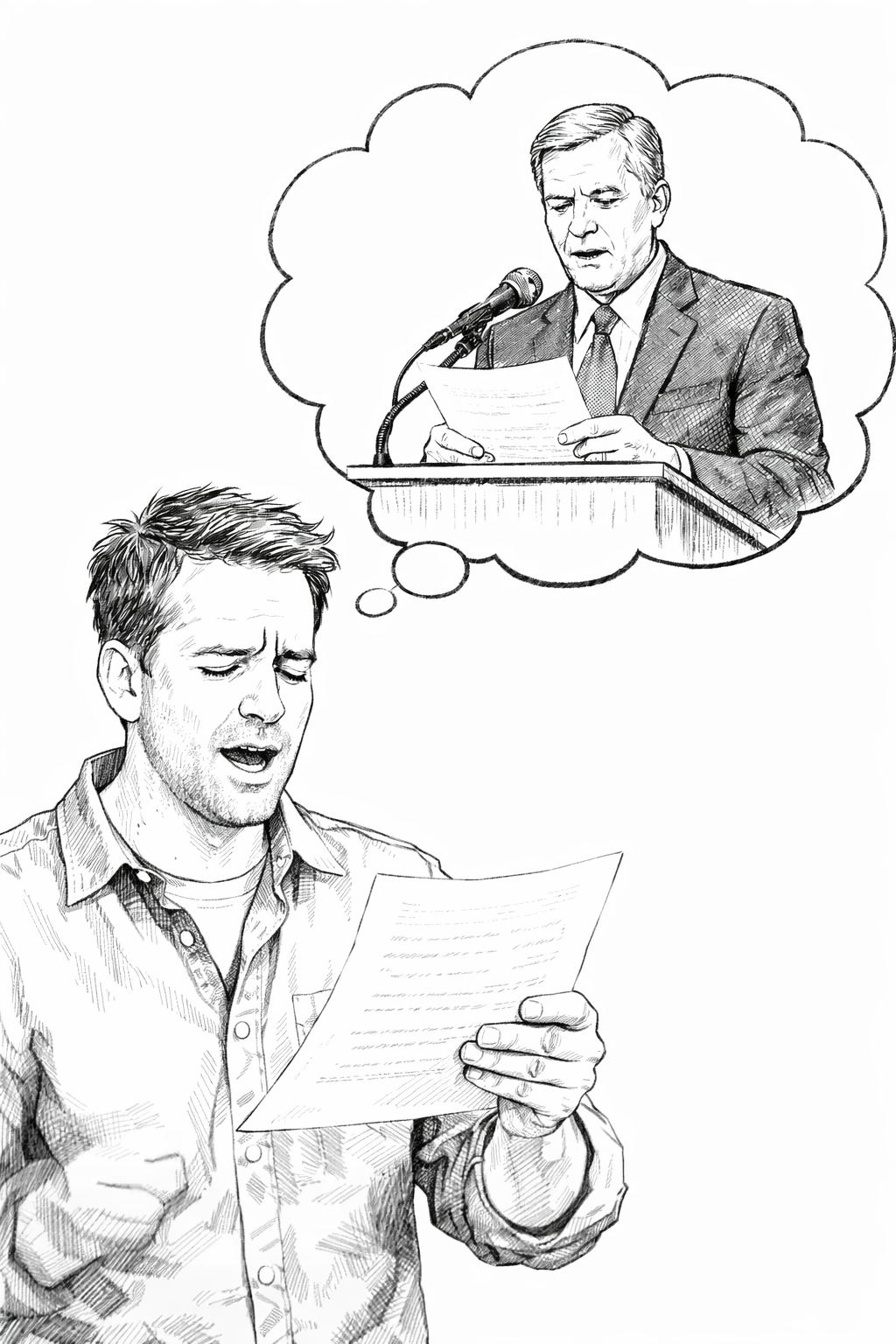

In a much ballyhooed Commencement Address at Duke University earlier this month, Jerry Seinfeld put on a master-class in framing — the art of organizing an argument to make its conclusions more lively and compelling.

The speech is worth reading, worth watching, and most of all, worth emulating.

To appreciate Seinfeld’s success here, you first have to see his advice to Duke’s graduates as the bag of clichés it is. Work hard? Pay attention? Fall in love? Seize opportunities? Keep a sense of humor?

How did such mundane content trigger so much praise and criticism? Because of the deftly arresting way Seinfeld frames his points. Throughout the speech, Seinfeld never simply decrees his life lessons. Rather, he sets them up, kind of like — well, exactly like — a comedian’s punchlines.

For instance, Seinfeld’s endorsement of hard work — “pure, stupid, no-real-idea-what-I’m-doing-here effort” — comes only after a two-paragraph bit roasting the undeserved glamour of “finding your passion.”

“The hell with passion,” he says. “It’s embarrassing. Just be willing to do your work as hard as you can with the ability you have.”

When he encourages graduates to “fall in love,” he again crosses up audience expectations. “It’s easy to fall in love with people,” he says. “I suggest falling in love with anything and everything, every chance you get” — like Bic pens, sneakers, and perfect pizza crust.

He even defends — quelle horreur — privilege! “Use your privilege!” he exhorts, which — for all its Culture War-coded language, is just another way of saying “take advantage of life’s opportunities,” which everyone would advise.

During this riff, Seinfeld drops the best line of his speech: “My point is we’re embarrassed about things we should be proud of and proud of things we should be embarrassed about.” The stadium responded with prolonged applause.

Finally, Seinfeld defends humor. Not only as humanity’s natural medicine against despair: “the most powerful, most survival-essential quality you will ever have or need to navigate through the human experience.” But also, explicitly, as more important than young people’s admirable desire to avoid “hurting other people’s feelings.”

“The slightly uncomfortable feeling of awkwardness,” he says, the “occasional discomfort,” the “occasional hard feelings,” are worth suffering in order “to have some laughs.”

Once again, Seinfeld’s audience — woke academics and campus snowflakes! — burst in to applaud his affable but defiantly bougie, anti-PC message.

Seinfeld’s lesson to young writers here — and to young conservatives in particular — is that thoughtful, counterintuitive framing can charge even the stodgiest ideas with new and electric appeal.

Until next week… keep writing!